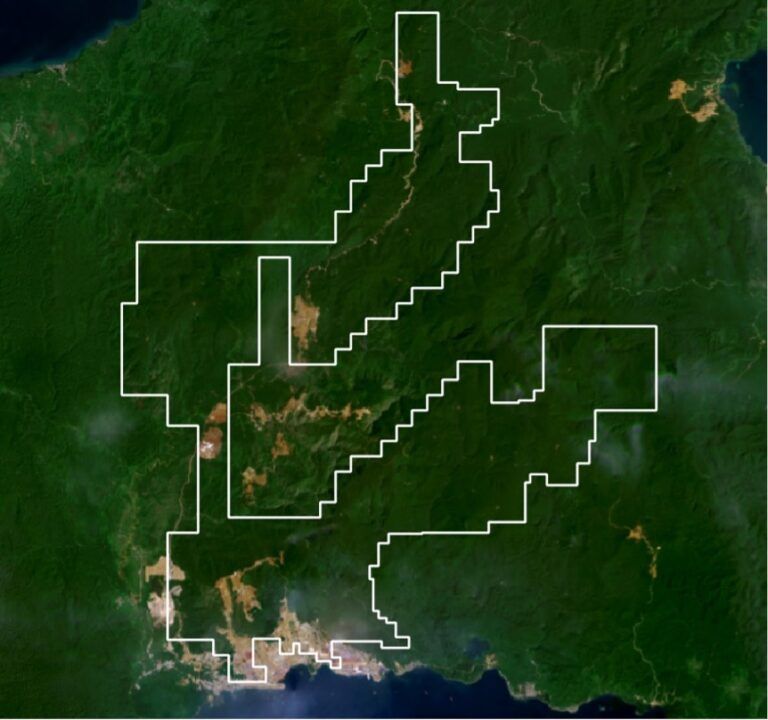

An aerial view of the Indonesia Weda Bay Industrial Park (IWIP), including captive coal plants and nickel smelting operations. Credit: Muhammad Fadli for CRI.

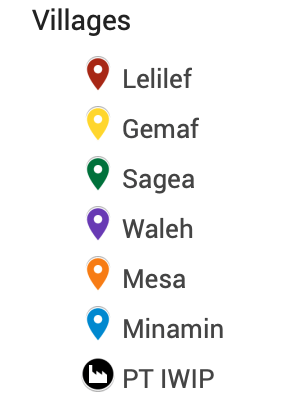

Max Sigoro, a 51-year-old Sawai fisherman, began fishing the blue waters near his coastal community, Gemaf, on the remote island of Halmahera in Eastern Indonesia, in his youth. For decades, he caught skipjack tuna and groupers, which fed his family and has been a major source of income. Today, because of pollution from smelting operations at the Indonesia Weda Bay Industrial Park (IWIP) and nickel mining in the area, Max’s catch has dropped significantly, making it harder to sustain himself and his family.

Before the mining, the fish stock was abundant, the sea was clear. Now, I can’t catch fish near [IWIP]. The water is dirty, and the security chases us away. The water pollution is from mining. There is oil in the water from the machines. Also, hot water from the power plants is polluting the ocean. Sometimes the water is reddish. We used to row our boats close to the shore to fish, now we have to go further out. It’s more dangerous to go further out and we have to calculate the tides. It’s also more expensive. The fish are the same size. But we worry about the fish being polluted.1Climate Rights International interview with Max Sigoro, February 8, 2023, Gemaf, North Maluku, Indonesia.

Maklon Lobe, a 42-year-old Sawai man from Gemaf, owned farmland within the current boundaries of IWIP, where he grew cocoa, sago, and nutmeg. Maklon told Climate Rights International that, without his permission, in 2018 representatives of IWIP cut down his trees, blocked the road to cut off access to his land, and began excavating his land. Maklon says he met with IWIP representatives multiple times between 2018 and August 2022 to discuss compensation. During this period, police officers visited his home “countless times,” demanding to know why he refused to sell his land to IWIP. Eventually, Maklon gave in. Despite holding a land certificate confirming his legal ownership of 38 hectares of land, IWIP only agreed to pay for eight hectares, taking the rest without compensating him.2Climate Rights International interview with Maklon Lube, February 10, 2023, Gemaf, North Maluku, Indonesia.

This report documents the environmental and human impacts of IWIP, a huge nickel smelting and processing project, and surrounding nickel mines in Halmahera. The construction and operation of IWIP and upstream nickel mining has devastated the lives of many Indigenous Peoples and other rural community members, like Max and Maklon, and caused significant harms to the local environment and global climate.

Climate Rights International interviewed 45 people living near nickel mining and smelting operations who described serious threats to their land rights, rights to practice their traditional ways of life, right to access clean water, and right to health due to the mining and smelting activities at IWIP and nearby nickel mining areas. Some companies, in coordination with Indonesian police and military personnel, have engaged in land grabbing, coercion, and intimidation of Indigenous Peoples and other communities, who are experiencing serious and potentially existential threats to their traditional ways of life.

Indonesia is the world’s largest producer of nickel, supplying 48 percent of global demand in 2022. Across the country, massive nickel industrial parks are being built, where nickel ore is refined into usable materials for industrial applications and consumer products. While for decades nickel has primarily been used in the production of stainless steel, demand has skyrocketed in recent years due to increasing use in renewable energy technologies, including in electric vehicle (EV) batteries. To meet the growing demand for EVs and other renewables, and in a scenario aligned with the Paris Agreement’s climate goals, global nickel demand is expected to increase roughly 60 percent by 2040.

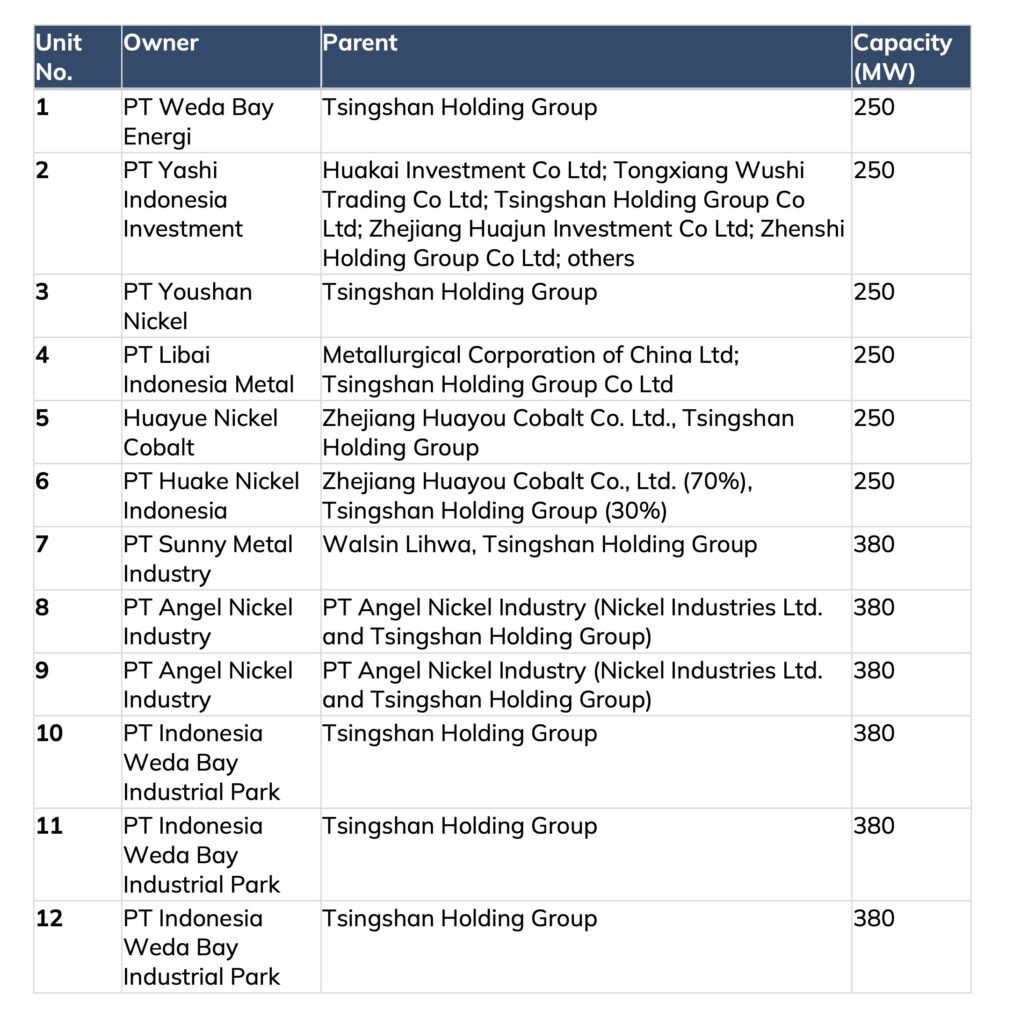

Perversely, although the purpose of the EV transition is to reduce the carbon footprint of the automobile industry, nickel smelting at IWIP has a massive carbon footprint. Instead of using plentiful renewable solar and wind power, IWIP has already built at least five captive coal-fired plants and ultimately will be home to twelve new coal-fired power plants. In total, these coal plants will provide an estimated 3.78 gigawatts per year of energy by burning low quality coal from Kalimantan on the island of Borneo. Once fully operational, they will use more coal than Spain or Brazil in a single year.

Indonesia’s President, Joko Widodo (popularly known as “Jokowi”), has made the nickel and battery industries the centerpiece of his plans for Indonesia’s economic development. In his November 2023 visit to the White House, it was the top agenda item in his talks with U.S. President Joe Biden.

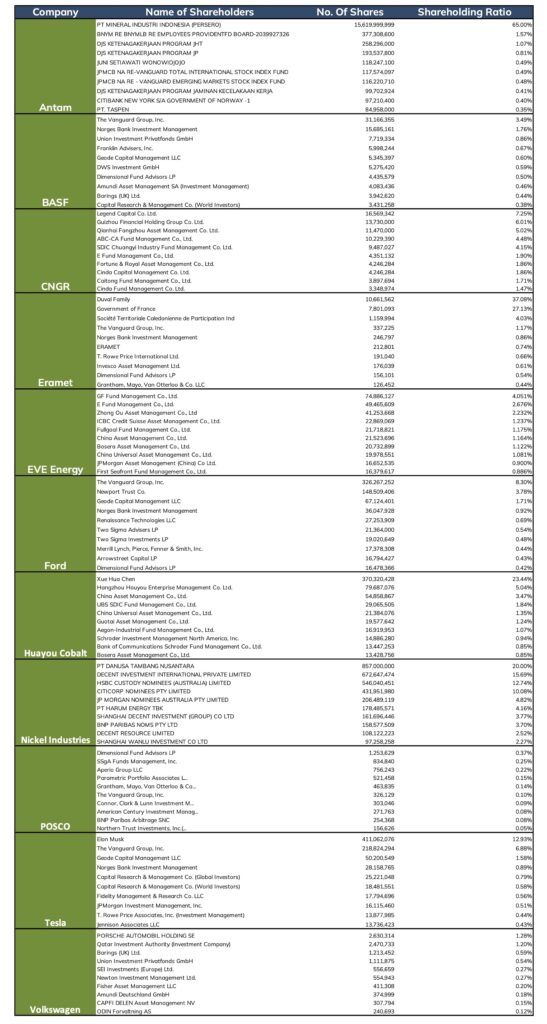

The transition to renewable energy is essential, but strong government regulation and oversight is necessary to ensure that the growing critical mineral industry and related supply chains do not replicate the appalling labor and environmental practices that have long characterized the extractive industries in Indonesia and around the globe. Electric vehicle companies, such as Tesla, Ford, and Volkswagen that have contracts to source nickel from Indonesia, including from companies that have operations at IWIP, should push for sustainable, just supply chains and call on the Indonesian government and mining and smelting companies to protect the land and other rights of Indigenous Peoples and communities in resource-rich areas, minimize deforestation, mitigate air and water pollution, and ensure that the rights of activists and local residents to organize and protest are upheld.

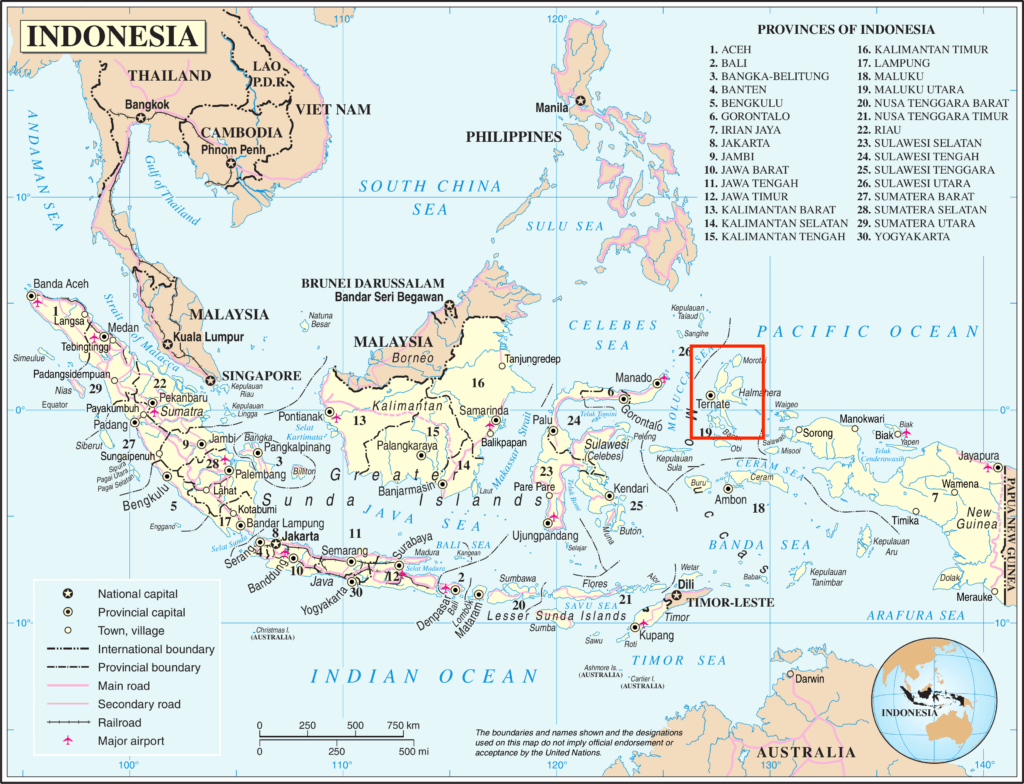

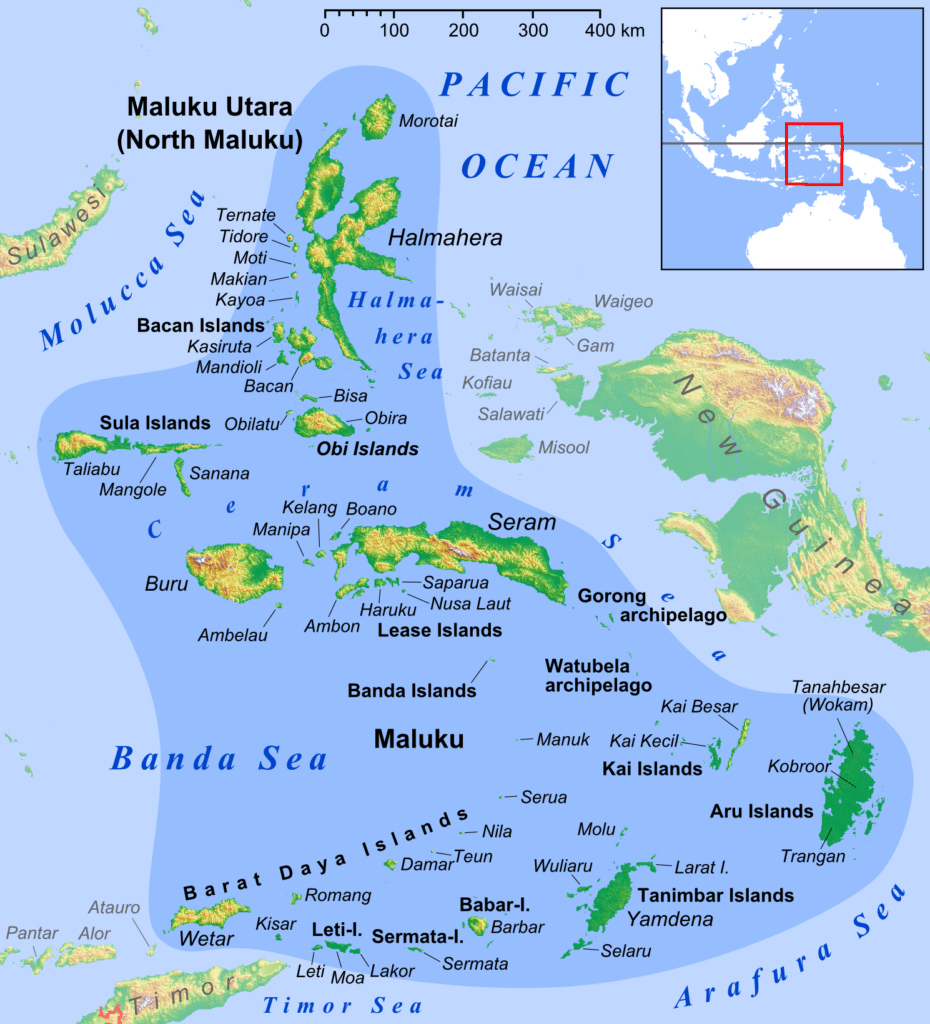

Halmahera Island in North Maluku province is one of the “Spice Islands,” home to nutmeg, mace, cloves, and other products that drove European colonial interest in the area starting in the 16th century. The island is largely forested, mountainous, and sparsely populated. The Maluku Islands are home to a diverse population, with approximately 28 ethnic groups and languages, including Sawai and Tobelo.

As in the colonial era, outside interests are again staking their claim on Halmahera’s natural resources. In 2018, construction began on IWIP, a 5,000-hectare, multi-billion-dollar industrial complex located in Lelilef Village, Central Halmahera, North Maluku, roughly three kilometers from Max Sigoro’s home in Gemaf. IWIP was built at breakneck speed, beginning operations in 2020, less than two years after the project was announced. The mountainous area just north of the industrial park is rich with nickel deposits.

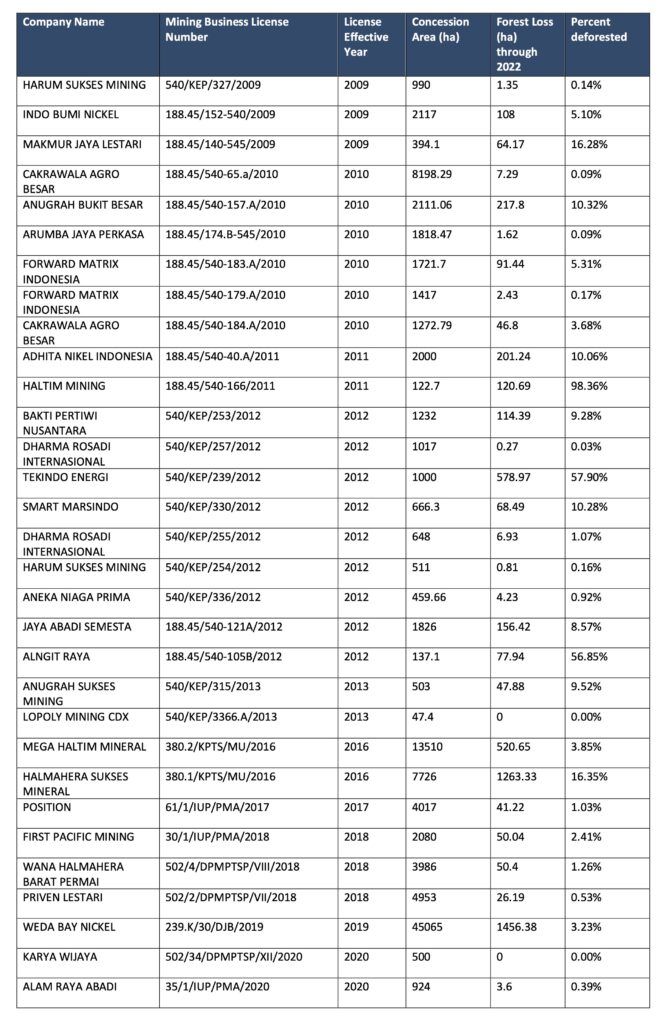

In addition to the greenhouse gas emissions from coal plants at IWIP, nearby nickel mining is a significant driver of deforestation, another contributor to the climate crisis and biodiversity loss. Using geospatial analysis, Climate Rights International (CRI) and the University of California, Berkeley, AI Climate Initiative determined that at least 5,331 hectares of tropical forests have been cut within nickel mining concessions on Halmahera, totaling a loss of approximately 2.04 metric tons of greenhouse gases (CO2e) previously stored as carbon in those forests.

Individuals interviewed by Climate Rights International reported that the process of land acquisition has been marred by land grabbing, little or no compensation, and unfair land sales. People living near IWIP have had their land taken, deforested, or excavated by nickel companies and developers without their consent. Some community members who refused to sell their land or contested the set land price offered experienced intimidation, received threats, and faced retaliation from company representatives, police officers, and members of the military. The arrival of the nickel industry has led to a growth in police and military presence in the villages near IWIP, including a Mobile Brigade for the Indonesian National Police and an Indonesian National Army outpost.

As the nickel industry transforms this region, both coastal and forest communities are experiencing existential threats to their livelihoods and traditional ways of life. For generations, communities living in Central and Eastern Halmahera have depended on natural resources to sustain themselves and their families as artisanal fisherfolks, farmers, sago-makers, and hunters. People interviewed by Climate Rights International reported that the nickel industry’s destruction of forests, acquisition of farmland, degradation of freshwater resources, and harm to fisheries has made it difficult, if not impossible, to continue their traditional ways of life.

For most of his life, Felix Naik, 65, used water from the Ake Doma River, a small river near Lelilef, for nearly everything. Yet since mining companies came to the area, he avoids using the water. Felix told Climate Rights International, “There is deforestation on the river upstream. So if it rains, the river turns dark brown and muddy,” indicating that the water is mixed with soil sediment from the upstream area, which may also indicate harmful heavy metal pollution.3W Wei et al., “Effects of Mining Activities on the Release of Heavy Metals (HMs) in a Typical Mountain Headwater Region, the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau in China,” Intl J Environ Res Public Health 15,9 (2018), doi: 10.3390/ijerph15091987 (accessed December 14, 2023). Felix has dug three wells to survive, but the water is not enough to support his family, so he must buy gallons of water every two to three days for IDR5,000 (US$0.33) per gallon.

Rampant deforestation, air and water pollution, and habitat destruction from nickel mining and smelting activities are seriously harming the environment. Nickel mining and smelting operations are threatening local residents’ right to safe, clean drinking water, as industrial activities and deforestation are polluting the waterways on which local communities depend for their basic needs. Community members are also concerned that increasingly common flooding events are linked to deforestation by nickel mining companies.

Residents in villages near IWIP also fear that newly developed health problems, including respiratory and skin problems, are related to pollution from the construction and operation of IWIP and its coal power plants. Although the public health studies needed to directly attribute the reported health problems to industrial nickel activities at IWIP are lacking, the types of health impacts reported are in line with what studies suggest may be expected with exposure to pollution from industrial sources and coal plants.

A lack of transparency or provision of basic information by companies and the Indonesian government is making the situation worse. Community members have difficulties accessing information about the consequences of industrial pollution on their health. Neither IWIP nor the government provides publicly available or accessible information on air and water quality to local residents.

Indigenous Peoples have the right to participate in decision-making in matters which would affect their rights. States should consult and cooperate in good faith in order to obtain their free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) prior to the approval of any project affecting their land or territories and other resources, particularly in connection with the development, utilization or exploitation of mineral, water or other resources. Yet, Indigenous Peoples interviewed by Climate Rights International in Central and East Halmahera repeatedly said that they were not told the purpose of land acquisition or any other details of the project by any nickel mining or smelting companies.

For Novenia Ambuea, an Indigenous rights activist in Minamin, East Halmahera, land represents her connection with her ancestors. In Novenia’s spare time, she and her husband manage their 2-hectare farm where they grow coconuts, nutmegs, bananas, and vegetables. Yet this way of life is threatened as Novenia’s land is now surrounded by mining concessions. Novenia told Climate Rights International,

The land comes from our parents. If we sold it, then we also sold our history and memories. Life in Minamin is about fishing and farming, since a very long time ago. We are fisherfolk, hunters, and farmers. Our life now is still the same but soon that will change.4Climate Rights International interview with Novenia Ambuea, March 24, 2023, Minamin, North Maluku, Indonesia.

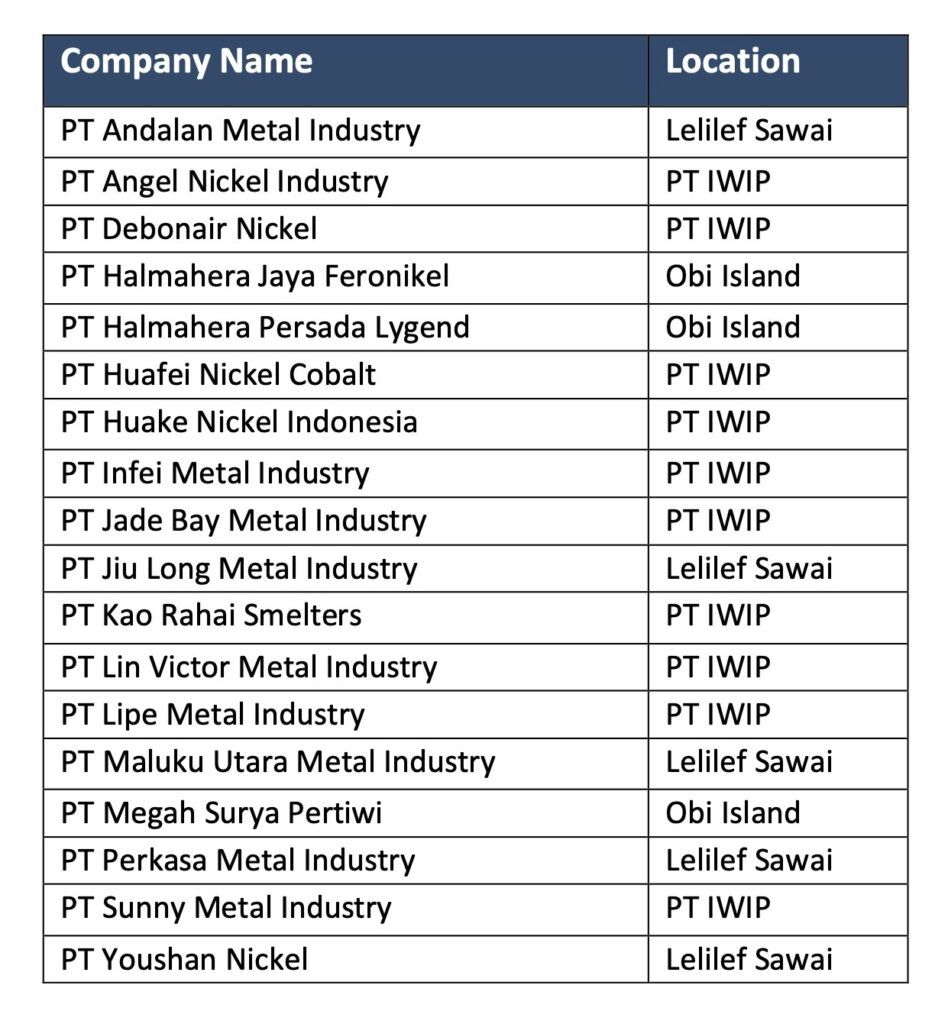

These harms to local communities and the environment are being driven by the activities of the dozens of domestic and foreign-based companies engaged in nickel mining and refining in Central and East Halmahera, including at IWIP.

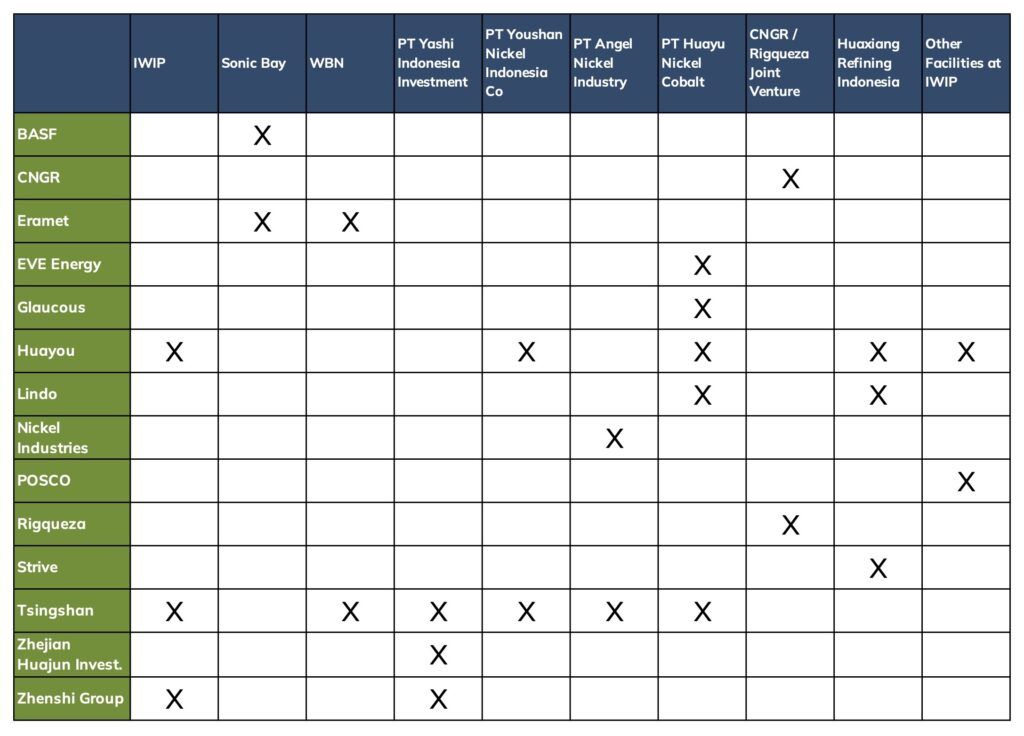

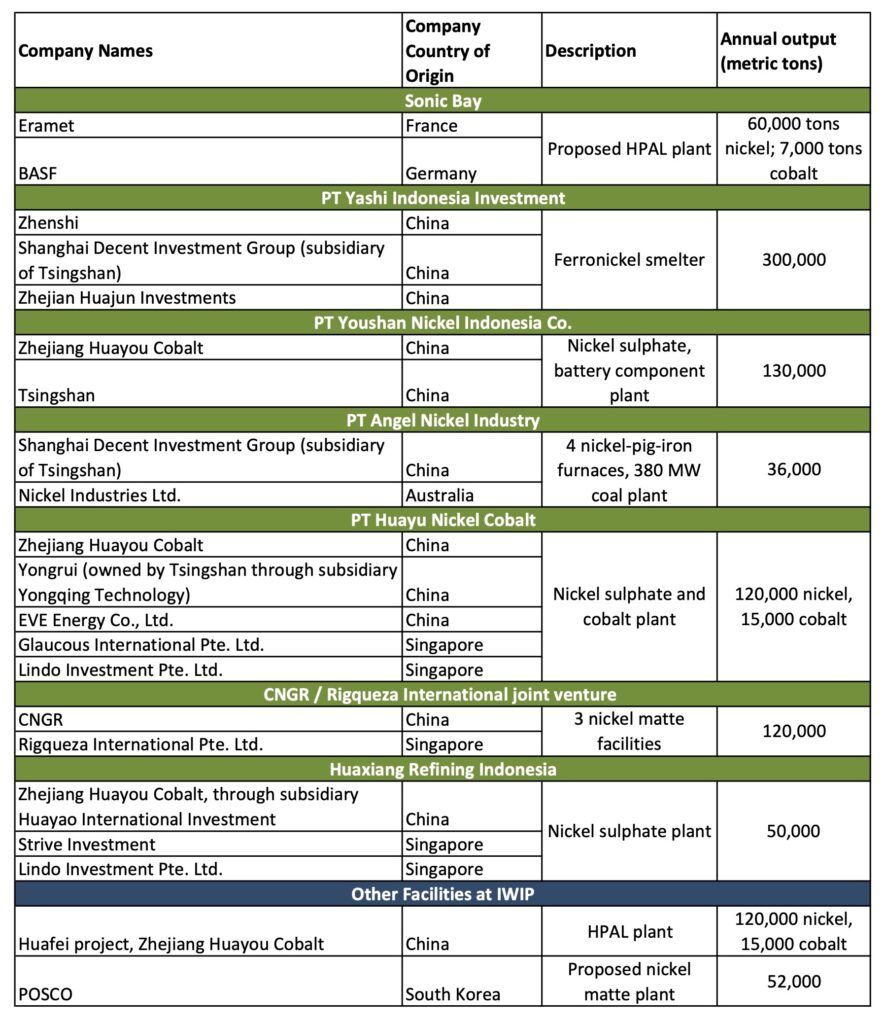

IWIP is a joint venture of three private companies headquartered in the People’s Republic of China: Tsingshan Holding Group, Huayou Cobalt, and Zhenshi Holding Group. In addition to these three shareholders, a growing number of companies have announced plans to build industrial facilities within IWIP to produce nickel materials needed for EV batteries. Eramet and BASF have announced plans to build a nickel and cobalt refining facility, called Sonic Bay, that would produce 67,000 tons of nickel and 7,500 tons of cobalt per year, using potentially dangerous high-pressure acid leach (HPAL) technology. In addition, South Korean giant POSCO has announced plans for a $441 million plant in IWIP with the capacity to produce 52,000 metric tons of refined nickel per year, enough for roughly one million EVs.

The Indonesian government is actively promoting the nickel industry over the wellbeing of its citizens. Over the past decade, the Indonesian government has enacted policies and laws to prioritize the growth of the nickel industry and weaken environmental protection and the rights of Indigenous communities. In doing so, it has failed to fulfill its obligation to protect and respect the rights of those affected by mining and smelting operations. The Indonesian government is also failing to protect the climate and mitigate climate change.

President Jokowi should strengthen laws and regulations to minimize the impacts of nickel mining and refining on communities, including on Indigenous communities. The Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources should ensure that mining companies follow strict mining operations procedures that respect the environment and human rights and should fully assess, monitor, and investigate alleged environmental pollution and make the findings of that investigation publicly available and accessible. The Ministry of Agrarian Affairs and Spatial Planning should immediately recognize Indigenous communities’ customary land and ensure that nickel mining and refining companies respect the rights of local and Indigenous communities. The Indonesian government should also immediately stop the permitting of all new coal plants, including captive coal plants used to power industrial areas.

Companies at IWIP and some nearby nickel mining companies are failing their human rights responsibilities under the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. The three main stakeholders in IWIP – Tsingshan, Huayou, and Zhenshi – should conduct due diligence to fully identify the harms caused by their operations and engage in mediation with impacted communities near the Indonesia Weda Bay Industrial Park regarding how best to remedy those harms. IWIP and nickel mining companies should fully and fairly compensate all community members, including Indigenous Communities, for their lands. Nickel companies should properly dispose of mine tailings to minimize environmental pollution and stakeholders at IWIP should take immediate steps to remedy water and air pollution caused by their operations. All companies must ensure that Indigenous Peoples are able to provide full FPIC as established by international human rights law. Companies that have not yet begun construction on proposed developments at IWIP, including Eramet, BASF, and POSCO, should pause developments until a full, independent investigation of the human rights, environmental, and climate impacts of the project is conducted.

To prevent climate catastrophe, project developers should immediately stop the construction of all new coal plants at the Indonesia Weda Bay Industrial Park and instead power industrial operations with renewable energy sources like wind or solar power. Companies should also take steps to minimize air, water, and soil pollution from industrial activities.

Electric vehicle companies such as Tesla, Ford, and Volkswagen that have contracts to source nickel from Indonesia, including from companies that have operations at IWIP, should immediately use their leverage to push suppliers to address harms to local communities and the environment, and if necessary, stop sourcing nickel from companies responsible for such abuses. EV companies should also increase transparency about their critical minerals supply chains by providing public information about all suppliers, including those involved in mineral mining, refining, smelting, and battery production. In addition, they should conduct regular, transparent, and genuinely independent audits of mines and facilities where critical minerals are mined and refined.

As noted by United Nations Secretary General António Guterres, “The extraction of minerals for a clean energy revolution must be done in a sustainable, fair & just way.”5A Guterres, X post, December 2, 2023, https://twitter.com/antonioguterres/status/1730994288551510362 (accessed December 2, 2023). Climate Rights International believes that the transition to electric vehicles is an essential part of the renewable energy and green transportation transition, but this transition will only be “green” and “just” if it respects human rights throughout the supply chain for materials and does not perpetuate the same abusive, climate-intensive practices followed for decades by extractive industries. Governments and regulators should also increase access to public transit and alternative methods of transport to decrease emissions from private vehicles, and mandate minimum levels of recycled content in EV batteries to decrease the demand for virgin critical minerals.

To IWIP and all nickel mining and smelting companies in Central and East Halmahera:

To the Indonesian government:

To electric vehicle companies:

AMAN – Aliansi Masyarakat Adat Nusantara (National Indigenous Communities Alliance)

AMDAL – Analisis Mengenai Dampak Ligkungan (Environmental Impact Assessment)

Beneficiation – The process of milling ore and separating out the small quantities of metal from the non-metallic materials

Captive coal plant – A coal-fired power plant that powers off-grid industrial activities and does not feed into the electricity grid.

CIPP – Comprehensive Investment and Policy Plan

Critical minerals – Also called transition minerals, these are mineral resources essential for clean energy technologies, economies, or national security

EIA – Environmental Impact Assessment

ESG – Economic, Social, and Governance

ESIA – Environment and Social Impact Assessment

FPIC – Free, Prior, and Informed Consent

FPM – PT First Pacific Mining

G20 – Group of Twenty

HPAL – High pressure acid leach

IMIP – PT Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park

IRMA – Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance

IWIP – PT Indonesia Weda Bay Industrial Park

JETP – Just Energy Transition Partnership

JV – Joint venture

Komnas HAM – Indonesian National Commission on Human Rights

LCA – Life cycle analysis

MHM – PT Mega Haltim Mineral

NDC – Nationally Determined Contribution to the Paris Agreement

Overburden – Rock, soil, or other material lying above a mineral deposit.

Scope 3 – Scope 3 emissions cover all indirect greenhouse gas emissions outside the control of a business or its direct energy sources that arise in a value chain (both upstream and downstream), such as emissions from the extraction and production of raw minerals

TDS – Total dissolved solids

UNFCCC – United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

WBN – PT Weda Bay Nickel

XUAR – Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region

This report examines the human, environmental, and climate impacts of nickel mining and smelting operations in Halmahera, North Maluku, Indonesia. Our research focused on communities living near the Indonesia Weda Bay Industrial Park, as well as communities in and around nickel mining concessions.

Climate Rights International conducted this research because local residents and community groups had reported human rights abuses, deforestation, forced displacement, and pollution as the result of the Weda Bay nickel project. The climate change and human rights consequences of the extraction of critical minerals is a key aspect of the transition to Net Zero. Indonesia is important because it is the world’s largest supplier of nickel, its nickel industry is growing at a rapid pace, and it has multiple large-scale nickel smelting industrial areas in various parts of the country. The Indonesia Weda Bay Industrial Park, which went into operation in 2022, is located in close proximity to multiple Indigenous communities, and has received less attention than other similarly-sized nickel industrial parks in Indonesia.

This report is based on information collected during field research in North Maluku between February and September 2023. Over the course of this research, Climate Rights International representatives visited the following villages and cities: Weda, Lelilef, Gemef, Fritu, Sagea, Waleh, Messa, Minamin, Tukur-Tukur, Saolat, and Ternate.

Climate Rights International interviewed 45 people living near nickel mines, concessions, or industrial areas for this research, including 26 men and 19 women. We did not interview any children. Thirty-nine community members interviewed for this report identified as Indigenous, including 20 Sawai and 19 Tobelo people.

All interviewees provided informed consent to participate in the interview. In some cases, we have given pseudonyms and withheld identifying information of interviewees to protect their identity over fears of retaliation. No financial incentives were provided to interviewees.

In addition, CRI also spoke with dozens of regional and international organizations on nickel operations in Indonesia.

To calculate deforestation levels, we partnered with researchers at the University of California, Berkeley Climate AI Lab to quantify the amount of forest lost within mining concessions. Researchers overlayed mining concessions in Indonesia using geospatial data available on the Indonesian Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources website on deforestation maps by Global Forest Watch, and were able to calculate forest loss within each mining concession across the country on an annual basis.

We also reviewed secondary resources, including peer reviewed literature, media reports, legal documents, and company reports. Climate Rights International also reviewed Indonesian laws and regulations.

Prior to the release of this report, Climate Rights International wrote to the Ministry of Agrarian Affairs and Spatial Planning, the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources, the Ministry of Environment and Forestry, the Ministry of Finance, the Coordinating Ministry of Maritime and Investment Affairs, the North Maluku Provincial Government, and the North Maluku Provincial Environmental Agency. Climate Rights International also wrote to 22 companies, including nickel mining, smelting, and electric vehicle companies. Copies of these letters and government or company responses may be found in Appendix I.

Map of Indonesia. Red box around Halmahera.

The world is undertaking a massive energy transition to mitigate the climate crisis and decrease greenhouse gas emissions. To do this, governments and companies are making major investments to move away from fossil fuels to renewable energy. To power new energy systems, critical minerals – including nickel, lithium, copper, and cobalt – are needed to build new technologies, including batteries, solar panels, and onshore and offshore wind farms.6United States Department of the Interior, “2022 Final List of Critical Minerals,” February 22, 2022, https://d9-wret.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/assets/palladium/production/s3fs-public/media/files/2022%20Final%20List%20of%20Critical%20Minerals%20Federal%20Register%20Notice_2222022-F.pdf (accessed March 27, 2023).

Historically, nickel’s primary use has been in the production of stainless steel. Now, nickel has been deemed a critical mineral due to its importance in solar infrastructure and rechargeable lithium-ion, nickel cadmium, and nickel metal hydride batteries. Nickel’s relative abundance, resistance to corrosion, high energy density, and large storage capacity make it particularly useful in batteries. Battery technology development is also projected to shift towards higher percentages of nickel in battery cathodes as an alternative to cobalt, which is primarily mined in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and has been linked with child labor, labor rights abuses, and armed conflict.7L Prause, “Chapter 10 – Conflicts related to resources: The case of cobalt mining in the Democratic Republic of Congo,” The Material Basis of Energy Transitions (2020): 153-167, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-819534-5.00010-6 (accessed April 1, 2023); Amnesty International, “Exposed: Child labour behind smart phone and electric car batteries,” January 19, 2016, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2016/01/child-labour-behind-smart-phone-and-electric-car-batteries/ (accessed April 1, 2023): RAID, “Exploitation of workers in DR Congo taints electric vehicles,” November 7, 2021, https://raid-uk.org/exploitation-of-workers-in-dr-congo-taints-electric-vehicles/ (accessed December 12, 2023).

To meet the growing demand for EV batteries and other renewable energy technologies and in a scenario aligned with the Paris Agreement goals, global nickel demand is expected to increase roughly 61 percent by 2040.8International Energy Agency, “The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions,” May 2021, https://www.iea.org/reports/the-role-of-critical-minerals-in-clean-energy-transitions/executive-summary (accessed April 5, 2023). The auto industry is – and will continue to be – responsible for a significant portion of that increased demand for nickel, as an average electric vehicle requires 39.9 kilograms of nickel.9Ibid.

Indonesia is the world’s largest producer of nickel and holds 21 percent of the 100 million metric tons of global nickel reserves.10Other countries with significant nickel deposits include Australia (21 million metric tons), Brazil (16 million metric tons), Russia (7.5 million metric tons), New Caledonia (7.1 million metric tons), Philippines (4.8 million metric tons), Canada (2.2 million metric tons), China (2.1 million metric tons), and the United States (0.37 million metric tons). Statista, “Reserves of nickel worldwide as of 2022, by country,” January 2023, https://www.statista.com/statistics/273634/nickel-reserves-worldwide-by-country/ (accessed April 4, 2023). In 2022, Indonesia supplied 48.8 percent of the world’s nickel.11IRENA, “Geopolitics of the Energy Transition: Critical Minerals,” July 2023, https://www.irena.org/Publications/2023/Jul/Geopolitics-of-the-Energy-Transition-Critical-Materials (accessed July 21, 2023).

Like other countries located near the equator, Indonesia is home to significant laterite nickel ore deposits, which are generally lower quality and found closer to the surface than the nickel sulfide deposits found in temperate countries, including the U.S., Canada, and Russia. Because of its lower quality, laterite nickel ore is significantly more carbon intensive to process into high-quality nickel that can be used in the production of batteries.12International Energy Agency, “GHG emissions intensity for class 1 nickel by resource type and processing route,” May 2021, https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/ghg-emissions-intensity-for-class-1-nickel-by-resource-type-and-processing-route (accessed April 5, 2023). In addition, large industrial areas in Indonesia where nickel ore is processed are powered by high-emitting coal-fired power plants, which have been constructed for the sole purpose of powering nickel processing operations.13For more information about coal use at the Indonesia Weda Bay Industrial Park, see Chapter VII on Climate Impacts.

During former President Suharto’s New Order regime, corruption was widespread and governance was heavily centralized. Uneven distribution of government and private resources created economic imbalances between Java and the rest of the regions, particularly Eastern Indonesia.14HY Prabowo and K Cooper, “Re-understanding corruption in the Indonesian public sector through three behavioral lenses,” Journal of Financial Crime, 23, 4 (2016): 1028-1062, http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/JFC-08-2015-0039; SHB Harmadi and A Adji, “Regional Inequality in Indonesia: Pre and Post Regional Autonomy Analysis,” TNP2K Working Paper, December 2020, https://www.tnp2k.go.id/download/11191WP%2050%20Regional%20Inequality%20in%20Indonesia.pdf (accessed October 16, 2023). These problems remain to date.15Corruption in Indonesia continues to be a serious problem. The country scored a 34/100 on Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index in 2022, and 92 percent of people surveyed in 2020 for the Global Corruption Barometer indicating they believed government corruption to be a big problem. Transparency International, “Indonesia: Country Data,” n.d., https://www.transparency.org/en/countries/indonesia (accessed December 12, 2023).

After the fall of the New Order era, which lasted from 1966 to 1998, the Indonesian government increased regional autonomy through the passage of laws enabling regional governments to better distribute welfare, manage their own budget and finances through regionally owned enterprises, and streamline bureaucracy.16For more information, see Law No. 22 on Regional Administration and Law No. 25 on Financial Balance Between Regional and Central Government, both of which were passed in 1999. S Usman, The SMERU Research Institute, “Regional Autonomy in Indonesia: Field Experiences and Emerging Challenges,” June 2002, https://smeru.or.id/sites/default/files/publication/regautofieldexpchall.pdf; SHB Harmadi and A Adji, “Regional Inequality in Indonesia: Pre and Post Regional Autonomy Analysis,” TNP2K Working Paper, December 2020, https://www.tnp2k.go.id/download/11191WP%2050%20Regional%20Inequality%20in%20Indonesia.pdf. In addition, decentralization led to the establishment of new provinces that reflect the distribution of development and welfare across the country.17Indonesia now has 38 provinces, compared to 27 under Suharto’s New Order. SD Negara and FE Hutchinson, “The Impact of Indonesia’s Decentralization Reforms Two Decades On,” 38, 3 (2021): 289-295, https://www.jstor.org/stable/27096079 (accessed August 28, 2023).

In recent years, control over the mining sector has fluctuated between the central and regional governments. The Mineral and Coal Mining Law, which was passed in 2020, redistributed power back to the central government to issue mining permits, leaving regional governments and local officials without the authority to approve, deny, or manage mining activities.18FQ A’yun and AM Mudhoffir, “Omnibus law shows how democratic process has been corrupted,” October 12, 2020, https://indonesiaatmelbourne.unimelb.edu.au/omnibus-law-shows-how-democratic-process-has-been-corrupted/ (accessed October 16, 2023); I Pratiwi and T Firmansyah, “Izin Pertambangan Diambil Alih Pemerintah Pusat,” December 11, 2020, https://ekonomi.republika.co.id/berita/ql5bva377/izin-pertambangan-diambil-alih-pemerintah-pusat (accessed October 16, 2023). The highly controversial Job Creation Law, commonly known as the Omnibus Law, was also passed in 2020 despite massive public protests, weakening environmental protections, workers’ rights, and Indigenous Peoples’ access to their customary land by simplifying and accelerating infrastructure development and other business activities.19Human Rights Watch, “Indonesia: New Law Hurts Workers, Indigenous Groups,” October 15, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/10/15/indonesia-new-law-hurts-workers-indigenous-groups (accessed July 7, 2022).

In July 2022, the central government, through the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources, issued regulations that gave regional governments the power to issue permits for domestic mining companies to extract non-metallic minerals, like coal or gravel.20P Guitarra, CNBC Indonesia, “Sah! Gubernur Sudah Bisa ‘Lagi’ Berikan Izin Pertambangan,” July 7, 2022, https://www.cnbcindonesia.com/news/20220707100201-4-353615/sah-gubernur-sudah-bisa-lagi-berikan-izin-pertambangan (accessed August 28, 2023). The central government retains the power to issue permits for all metallic minerals, including nickel, and to issue permits to and monitor international companies.

For more than a decade, the Indonesian government has been taking steps to ban the export of nickel ore in an attempt to develop the country’s domestic mineral refining industry and boost export values. In 2009, the government passed Law No. 4 on Coal and Mineral Mining, which stipulated that companies with a mining business license or special mining business permit were required to process and refine mining products domestically within five years, effectively introducing a ban on the export of ore starting in 2014.21Law No. 4 of 2009 on Coal and Mineral Mining, https://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Details/38578/uu-no-4-tahun-2009 (accessed September 19, 2023). In 2014, a Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources regulation postponed the ban on the export of mineral ore until 2017.22Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources, 2014, https://jdih.esdm.go.id/index.php/web/result/39/detail (accessed September 19, 2023). After a series of additional postponements, the nickel ore export ban was finally implemented in 2020.

In a case brought by the European Union, the World Trade Organization (WTO) found in November 2022 that Indonesia’s ban on export of nickel ore violates article XI:1 of the 1994 General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade.23World Trade Organization, WT/DS592/R, “INDONESIA – MEASURES RELATING TO RAW MATERIALS,” November 30, 2022, https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/FE_Search/FE_S_S009-DP.aspx?language=E&CatalogueIdList=290011,290012,278387,273530,270196,259634,259248&CurrentCatalogueIdIndex=0&FullTextHash=&HasEnglishRecord=True&HasFrenchRecord=True&HasSpanishRecord=True (accessed November 28, 2023). The Indonesian government rejected this decision and promptly appealed the WTO’s ruling.24Reuters, “Indonesia appeals WTO ruling in nickel dispute against EU,” December 12, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/article/indonedia-eu-nickel/indonesia-appeals-wto-ruling-in-nickel-dispute-against-eu-idUSKBN2SW1PR (accessed March 15, 2023). As of the time of writing, the appeal had not been heard by the WTO’s appellate body, and Indonesia’s nickel ore export ban remains in place.

In January 2023, Indonesian Minister of Investment Bahlil Lahadalia announced that the country is considering forming an “OPEC-style cartel” for nickel and other raw materials used in battery production.25J Guild, “Indonesia wants more than a nickel for natural resources,” January 26, 2023, https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2023/01/26/indonesia-wants-more-than-a-nickel-for-natural-resources/ (accessed November 30, 2023). A June 2023 International Monetary Fund report on Indonesia notes that foreign direct investments to Indonesia, in particular from China and Hong Kong, have increased since Indonesia implemented the export ban on nickel ore.26International Monetary Fund, “Indonesia: 2023 Article IV Consultation-Press Release; Staff Report; and Statement by the Executive Director for Indonesia,” June 25, 2023, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2023/06/22/Indonesia-2023-Article-IV-Consultation-Press-Release-Staff-Report-and-Statement-by-the-535060 (accessed November 30, 2023).

Nickel deposits were discovered in Halmahera in 1996 and plans to mine nickel in the region began in the late 1990s. In early 1998, PT Weda Bay Nickel (WBN), a multinational corporation, signed a contract with the Indonesian government to explore for and eventually mine nickel.27The shareholders of Weda Bay Nickel have changed over time. Currently, Strand Minerals (in which Tsingshan Holding Group holds a 57 percent stake and Eramet holds a 43 percent stake) holds a 90 percent stake in WBN, and PT Antam holds the remaining 10 percent. Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources, “Weda Bay Nickel,” https://modi.esdm.go.id/portal/detailPerusahaan/8025 (accessed November 30, 2023). At the time, the concession granted to WBN Nickel was the largest mining concession in Halmahera, comprising nearly 55,000 hectares of land, with more than 35,000 hectares located inside Protected Forests, recognized under the 1999 Law No. 41 on Forestry.28As of 2023, the Weda Bay Nickel concession is 45,065 hectares. S Saturi, “Weda Bay Nickel, Berkonflik dengan Masyarakat Adat, Hutan Lindung pun Terancam,” Mongabay, June 7, 2013, https://www.mongabay.co.id/2013/06/07/weda-bay-nickel-berkonflik-dengan-masyarakat-adat-hutan-lindung-pun-terancam/ (accessed September 25, 2023); Ministry of Energy and Minerals Resources, “Minerba One Map Indonesia,” https://momi.minerba.esdm.go.id/public/ (accessed March 2, 2023).

However, the 1997-98 Asian financial crisis, which triggered the fall of President Suharto and his authoritarian New Order regime, led to years of negative and stagnant economic growth and stalled investments in Indonesia.29AD Ba, “Asian Financial Crisis,” Britannica, October 6, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/money/topic/Asian-financial-crisis (accessed November 30, 2023); East-West Center, “Indonesia in Crisis,” May 1998, https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/28415/api036.pdf (accessed November 30, 2023). In addition to the financial crisis, the sectarian conflict described below in Chapter II meant that the entire mining operation was put on hold until the mid-2000s.

The Weda Bay Nickel project began picking up steam again after Eramet gained majority control of the project in 2006. Following the 2010 release of Eramet-PT Weda Bay Nickel’s Exploration and Development Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA), a report by Earthworks, a US-based environmental NGO, found that the WBN project was likely, “to harm aquatic biodiversity in the streams, rivers and the ocean for extended periods of time.”30While Climate Rights International is not aware of an online copy of the ESIA, we have a copy on file. Earthworks, “Supplemental Biodiversity Review of Weda Bay Nickel Project,” July 2010, https://earthworks.org/files/publications/EW_review_WedaBayNickel_biodiversity.pdf (accessed July 10, 2023). The report also predicted that the project was likely to destroy large areas of protected tropical forest and that additional social and water quality impacts would also be severe, suggesting that, “the risks of proceeding with such a project are extremely high and a precautionary approach dictates that the project not proceed.”31Ibid.

In 2015, President Jokowi announced plans to build up Indonesia’s downstream minerals markets by incorporating nickel and EV production into the 2015-2035 national industrial master plan, setting the stage for the development of several large nickel industrial parks in the country, including IWIP.32Ministry of Industry, “INDONESIA: National Industry Development Master Plan (RIPIN) 2015-2035 (Government Regulation No. 14/2015 of 2015),” https://policy.asiapacificenergy.org/node/4174 (accessed September 25, 2023).

The Indonesia Weda Bay Industrial Park (IWIP) is a 5,000-hectare integrated smelter mega-project located in Lelilef Village, Central Halmahera, North Maluku. IWIP is a joint venture between three private Chinese companies, Tsingshan Group, Huayou Cobalt, and Zhenshi Group, and was designated in 2020 as a “national strategic project” by the Indonesian government. The concept of national strategic projects was announced by President Jokowi in 2016 and prioritizes large-scale economic development projects across the country. These projects receive special benefits, including accelerated land acquisition and a guarantee that projects will not face political barriers – a guarantee that some believe has led to an increase in land conflicts between project developers and local communities, including Indigenous Peoples, and serious environmental damage.33A Barahamin, “‘Infrastructure-first’ approach causes conflict in Indonesia,” China Dialogue, May 11, 2022, https://chinadialogue.org.cn/en/business/infrastructure-first-approach-causes-conflict-in-indonesia/ (accessed September 26, 2023).

IWIP began construction in August 2018 and nickel smelting operations at the industrial park began less than two years later in April 2020.34Reuters, “Tsingshan and Eramet’s Weda Bay nickel project starts production,” April 30, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-indonesia-nickel-idUSKBN22C1UK (accessed September 15, 2023). IWIP also provides space for tenants to process ferronickel, ferrochrome, stainless steel, nickel for electric vehicle batteries, and hydrometallurgical plants. (For a fuller discussion on the companies operating at IWIP see Chapter VIII on Corporate Actors.)

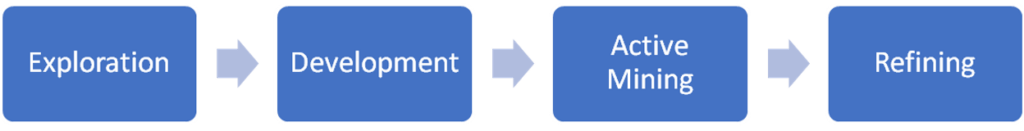

Once a nickel deposit is identified, it must go through a multi-step process to be extracted and refined into a usable mineral. As shown in Figure 1, the process for nickel mining and refining includes exploration, development, active mining, and refining. This process can pose serious threats to nearby communities and the environment.

In the first stage of the mining process, a company conducts exploratory activities to determine the location, quality, and value of the ore deposit. Laterite nickel deposits, such as those found in Indonesia, are near the Earth’s surface, with nickel making up only a small percentage of the ore. Nickel ore deposits in Central Halmahera are typically between 10-20 meters deep and range from 1.2 to 2.5 percent of the earth collected.35PT. ERM Indonesia, “Eramet-PT Weda Bay Nickel Exploration and Development ESIA,” February 2010, page I-10, accessed March 14, 2023). The exploration phase may include surveys, field studies, and drilling of test boreholes to determine the quantity of nickel deposits.36Environmental Law Alliance Worldwide, “Guidebook for Evaluating Mining Project EIAs,” July 2010, https://www.elaw.org/files/mining-eia-guidebook/Full-Guidebook.pdf (accessed February 22, 2023).

In the development phase, a company constructs mining roads, brings in heavy equipment and machinery, secures necessary permits, and acquires land from landowners or the state. The company must also build substantial infrastructure to support mining operations, including employee housing, processing facilities, and utilities. In the case of WBN in Central Halmahera, this step included construction of an airport near the town of Lelilef and a port to transport ore and refined nickel. The development phase includes the clearing of land or forests to prepare for mining operations.

Active mining is defined as the physical extraction of a mineral deposit from the earth. Because laterite nickel deposits are located near the surface, they are most easily accessible through open pit mining, a type of strip mining where layers of topsoil, overburden, and ore are removed. This requires the use of heavy equipment, including excavators, bulldozers, and trucks. Open pit mining poses serious threats to the local environment, including water and air pollution, permanent habitat loss, and increased risk of erosion and landslides. This phase also includes the disposal of waste rock and tailings, often in tailing ponds, which can pollute water resources with heavy metals and toxins if not managed properly.37For examples of the risks of exposure to pollutants in mine tailings, see: J Liu et al., “Risks to Human Health of Exposure to Heavy Metals through Wheat Consumption near a Tailings Dam in North China,” Pol J Environ Stud 32,4 (2023): 3195-3207, https://doi.org/10.15244/pjoes/163442; VM Ngole-Jeme and P Fantke, “Ecological and human health risks associated with abandoned gold mine tailings contaminated soil,” PLoS One 12,2 (2017), doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172517; R Liu et al., “Accidental Water Pollution Risk Analysis of Mine Tailings Ponds in Guanting Reservoir Watershed, Zhangjiakou City, China,” Int J Environ Res Public Health 12,12 (2015): 15269-15284, doi: 10.3390/ijerph121214983; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, “Superfund Site: BIG RIVER MINE TAILINGS/ST. JOE MINERALS CORP.,” n.d., https://cumulis.epa.gov/supercpad/SiteProfiles/index.cfm?fuseaction=second.Healthenv&id=0701639 (accessed December 6, 2023).

While outside of the scope of this report, the active mining phase ends with reclamation and closure plans, which are key to ensuring the mine does not have devastating environmental and social impacts after mining operations cease.

Once ore is extracted from the deposit, it is transported to a processing facility where it is refined. Refining, or beneficiation, is the process of milling ore and separating out the small quantities of metal from the non-metallic materials.38Ibid. Because of Indonesia’s ban on ore exports, ore extraction is exclusively done at domestic processing facilities and smelters. For nickel ore mined in Halmahera, it is largely transported to IWIP to be processed.

While there are multiple ways to refine nickel ore, conventional refining involves the grinding of ore into small particles, heating the materials in a rotary kiln, and extracting the metallic minerals through smelting.39E Keskinkilic, “Nickel Laterite Smelting Processes and Some Examples of Recent Possible Modifications to the Conventional Route,” Metals 9,9 (2019), https://doi.org/10.3390/met9090974 (accessed April 10, 2023). High-pressure acid leach (HPAL) is an energy-intensive process used to separate nickel and cobalt from low-quality laterite nickel ores to obtain high-quality battery-grade nickel. HPAL operates by mixing milled nickel ore and an acid in a container where it is subjected to extremely high temperatures and pressures.40H Ribeiro et al., S&P Global, “Rising EV-grade nickel demand fuels interest in risky HPAL process,” March 3, 2021, https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/market-insights/blogs/metals/030321-nickel-hpal-technology-ev-batteries-emissions-environment-mining (accessed December 5, 2023). Currently, French mining company Eramet and German chemical giant BASF have plans to develop a USD$2.6 billion HPAL plant in the Indonesia Weda Bay Industrial Park (for more, see Chapter VI).41As of December 2023, neither BASF nor Eramet have made a final investment decision about the project, according to statements provided by the two companies (see Appendix I). BASF, “BASF and Eramet partner to assess the development of a nickel-cobalt refining complex to supply growing electric vehicle market,” December 15, 2020, https://www.basf.com/global/en/media/news-releases/2020/12/p-20-388.html (accessed December 6, 2023).

At each stage of the nickel mining and refining process, industrial operations pose significant and long-lasting threats to ecosystems, biodiversity, and water resources. Open-pit mining is one of the most environmentally destructive forms of mining and can lead to permanent habitat destruction without proper remediation efforts. Mining is linked with erosion, increased risk of landslides, and flooding.42Frank Lehmkuhl and Georg Stauch, “Anthropogenic influence of open pit mining on river floods, an example of the Blessem flood 2021,” Geomorphology 421 (2023), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2022.108522, accessed April 9, 2023; Tao Chen et al., “Landslide mechanism and stability of an open-pit slope: The Manglai open-pit coal mine,” Frontiers in Earth Science (2023), doi: 10.3389/feart.2022.1038499, accessed April 9, 2023. Mining operations also drive deforestation; more than 1,900 km2 of forest were lost to industrial mining in Indonesia between 2000 and 2019, an area one and half the size of Los Angeles or almost three times as large as the city of Jakarta.43S Giljum et al., “A pantropical assessment of deforestation caused by industrial mining,” PNAS 119, 38 (2022), https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2118273119 (accessed December 6, 2023). Deforestation is a significant contributor to climate change, as carbon stored in biomass is released as carbon dioxide in the atmosphere when it is cut.

The economic crisis of the late 1990s had a significant impact on economic, political, and social conditions in Indonesia. The crisis contributed to the fall of Suharto and then played a part in triggering violent conflicts in several parts of the country, including the Maluku island chain.44J Bertrand, “Nationalism and Ethnic Conflict in Indonesia,” Cambridge University Press, https://books.google.co.id/books?id=2oZQRuT78JIC&printsec=frontcover&hl=id#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed December 6, 2023).

The Malukus experienced escalating conflict beginning in early 1999 until the signing of the Malino II Charter on February 13, 2002.45The 2002 peace process was led by the Indonesian central government. U.S. Embassy of the Republic of Indonesia, “The Moluccas Agreement in Malino (Malino II) Signed to End Conflict and Create Peace in the Moluccas,” February 14, 2002, https://www.peaceagreements.org/viewmasterdocument/579 (accessed December 6, 2023).

UN RC Indonesia, “UN Consolidated Inter-Agency Appeal for the Maluku Crisis 16 Mar – 30 Sep 2000,” March 2000, https://reliefweb.int/report/indonesia/un-consolidated-inter-agency-appeal-maluku-crisis-16-mar-30-sep-2000-0 (accessed December 6, 2023). Sectarian conflict, particularly on Ambon and Halmahera Islands, manifested itself in collective acts of ethno-political violence using religious symbols.46F Mursyidi, “The ambivalent role of religion in the Ambon conflict,” November 6, 2018, https://crcs.ugm.ac.id/the-ambivalent-roles-of-religion-in-the-ambon-conflict/ (accessed December 6, 2023).

Bertrand, Jacques (2004). Nationalism and ethnic conflict in Indonesia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-52441-5. As commercial, political, and criminal factions, long organized around religious identities, jockeyed for power in a changing landscape, conflict broke out largely between Christian and Muslim militias, but with many civilian casualties.

On Halmahera, relevant economic pressures included government plans to bring in up to 68,000 transmigrants from other parts of the country, the expansion of plantation agriculture and the development of the Nusa Halmahera Mineral gold mine in the subdistrict of Kao.47 CR Duncan, “Violence and Vengeance: Religious Conflict and its Aftermath in Eastern Indonesia,” Chapter 2, 2013, Cornell University Press, ISBN 978-0801479137. The conflict in North Maluku was largely between the “Laskar Putih” (white warriors), primarily ethnic Makian, Tidore, and Muslim militants from Java and other parts of Indonesia, and the “Laskar Kuning” (yellow warriors), primarily Muslim supporters of the Ternate sultanate and ethnic Kao people, a predominately Christian group with some Muslim members.48 CR Duncan, “Violence and Vengeance: Religious Conflict and its Aftermath in Eastern Indonesia,” Chapter 2, 2013, Cornell University Press, ISBN 978-0801479137; A Harsono, “Race, Islam and Power,” May 2021, Monash University Publishing, ISBN 978-1925835090; Lestari, Dewi Tika, 2019, Religious Conflict Transformation through Collective Memory and the Role of Local Music. Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research (ASSEHR), Volume 187: 119-123. The names Laskar Putih and Laskar Kuning originated from the color of the headbands worn by members of each group.

A 2000 Human Rights Watch report described how security forces deployed in the Malukus aggravated the situation: “Distrust of security forces is widespread, in large part because some members of military and police units have broken ranks and taken sides in the conflict. There have long been reports that army and police weapons and ammunition have found their way into the hands of partisans, but reports of direct participation in the violence by members of the armed forces are now increasingly common, with Christian soldiers supporting Christian groups and Muslim soldiers supporting the Muslim side.”49Human Rights Watch, “Moluccan Islands: Communal Violence in Indonesia,” May 31, 2022, https://www.hrw.org/news/2000/05/31/moluccan-islands-communal-violence-indonesia (accessed October 25, 2023).

The conflict, which remains one of the country’s most violent in the post-Suharto era, killed more than 10,000 people and displaced an estimated 700,000.50 A Harsono, “Race, Islam and Power,” May 2021, Monash University Publishing, ISBN 978-1925835090; Lestari, Dewi Tika, 2019, Religious Conflict Transformation through Collective Memory and the Role of Local Music. Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research (ASSEHR), Volume 187: 119-123. Despite de-escalation in 2002, violence remains a potentially serious risk.51M Björkhagen, “The Conflict in the Moluccas: Local Youths’ Perceptions Contrasted to Previous Research,” 2013, https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1483753/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed October 25, 2023). In addition, the involvement of military and police forces in the conflict is likely to influence how local communities in Central and East Halmahera experience the increased presence of military and police brigades in and around IWIP and other nickel mining areas.

The following section documents the many ways that nickel mining and smelting activities have threatened land rights of local communities in Central and Eastern Halmahera. Individuals interviewed by Climate Rights International reported that the process of land acquisition has been marred by land grabbing, little or no compensation, unfair land sales, and a failure to obtain free, prior, and informed consent from affected communities. In some cases, individuals faced intimidation or retaliation for refusing to sell their land or for opposing the nickel industry.

Under Indonesian law, an appraised value of a plot of land must be “adequate and fair to the entitled party,” and valuations must include structures, plants, objects, and other losses such as loss of income.52Law No. 2 of 2012, https://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Home/Details/39012. In addition, throughout Indonesia, regional governments set a base land tax value, calculated on a per square meter basis, through Ministry of Finance regulation No. 150 of 2010, which regulates the Land and Business Tax.53The Land and Building Tax are calculated based on the ’Zone’, which varies between each province. For example, the more strategic the location, the more expensive the land price. Ministry of Finance Regulation No. 150 of 2010, https://jdih.kemenkeu.go.id/fulltext/2010/150~PMK.03~2010Per.htm. This tax value does not include the value of crops or underlying minerals. The additional value of the land beyond the base tax value, including compensation for crops or buildings, is usually determined by both landowners and acquirers. In more developed parts of the country, such as Java, residents can find the tax value on the Regional Revenue Agency website.54For the neighboring province of Ambon, the province is divided into eight zones, each with a different Land and Building Tax amount, ranging between IDR200,000-IDR6,000,000 ($13-$390) in 2022. Ambon Mayoral Decree, August 2022, http://jdih.ambon.go.id/uploads/lampiran/2022sk8110597.pdf. However, online information is not posted for underdeveloped regions, including North Maluku province, so local residents are not able to easily access the tax value.55Bapenda Maluku Utara (Revenue Agency), https://bapendamalut.id/ (accessed December 6, 2023). Because of this lack of information regarding the base value of the land for tax purposes, residents in North Maluku are unable to ascertain how a proposed land sale price compares to base market value. Climate Rights International wrote to the Ministry of Finance seeking information on how the Ministry values land and how residents in North Maluku and other less developed regions can access this information, but they did not respond.

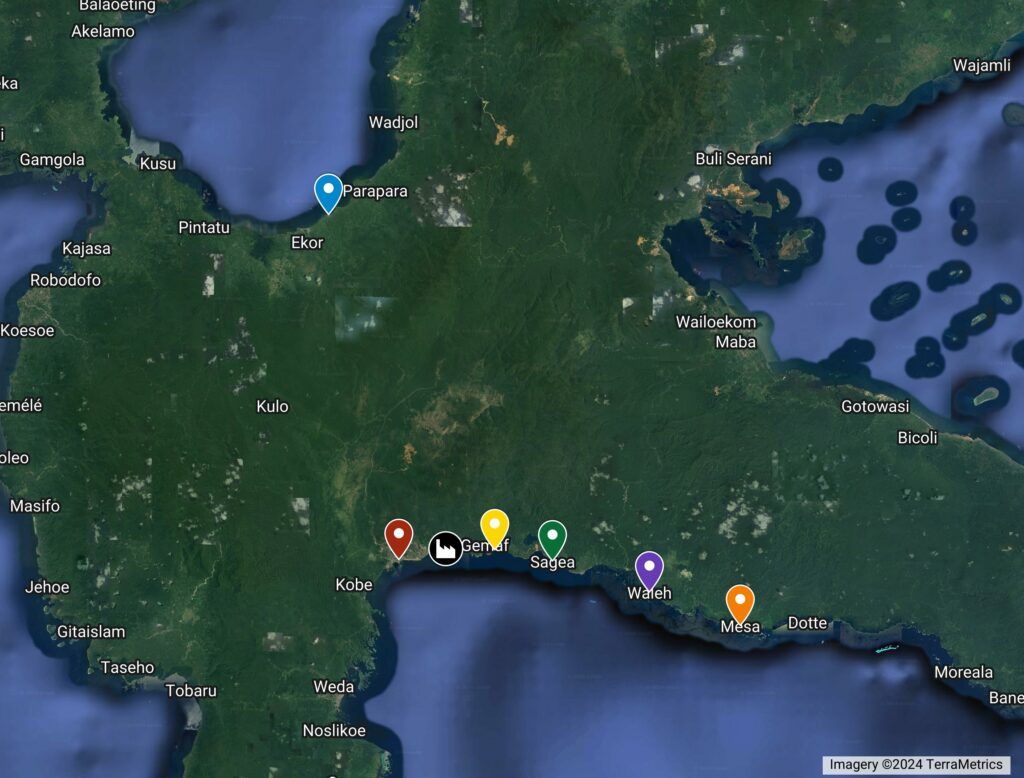

Villages near IWIP. Map data: Google, TerraMetrics.

Community members living near the Indonesia Weda Bay Industrial Park told Climate Rights International that their land had been taken, deforested, or excavated by IWIP without their consent. In some cases, land was taken from individuals who held land certificates confirming their legal ownership, while in other instances customary land held by Indigenous groups was summarily grabbed. In other cases, landowners were only compensated for a portion of their land.

In addition, local residents reported that nickel companies cut down or otherwise destroyed natural features, such as coconut trees, that were used to identify and demarcate boundaries between plots of land to expedite the land acquisition process.

Yulius Burnama, 74, said that IWIP representatives grabbed two hectares of his land in Lelilef to expand the airport in January 2019. Under Law No. 24 of 1997, if ownership of a plot of land cannot be confirmed through land registration, then the physical control of that land for twenty years or more can be used as the basis for recording land ownership. While Yulius did not hold a formal land certificate, which is common in less developed parts of Indonesia like North Maluku, he built fishing ponds on the land in 1995 and held the land for 24 years without dispute. For this reason, Yulius claimed legal ownership of the two-hectares and fishing ponds. Yulius said that all of the 600,000 fish in his three ponds died as a result of IWIP clearing his land and destroying the fishing ponds.

Yulius first complained to IWIP management on May 24, 2019, about the taking of his land. On May 26, 2019, Yulius met with the External Relations division of IWIP at the Central Halmahera Police Headquarters. According to a legal complaint later filed by Yulius and shared with Climate Rights International, both Yulius and IWIP agreed that Yulius and his family would not protest or take action that would disrupt IWIP’s construction or operations in exchange for compensation that would be provided after he filed a written complaint with IWIP’s management, which he did a few days after the meeting. In September 2021, he still had not received any compensation, so Yulius hired a lawyer to file a legal complaint against IWIP. At the time of writing, IWIP had not provided compensation.

They [the police and village leader] said the company has paid for the land, which I never received. I even hired a lawyer to settle this case, but so far nothing.56Climate Rights International interview with Yulius Burnama, May 12, 2023, Lelilef, North Maluku, Indonesia.

Jeffry, a 33-year-old trained lawyer from East Halmahera, owned a two-hectare plot of land in Gemaf, Central Halmahera, within the current boundaries of IWIP. Jeffry told Climate Rights International that IWIP began excavating and deforesting his land without his consent and prior to any discussion of a land sale. After learning that his land was being destroyed by developers, Jeffry said he had protested the destruction of his land to IWIP. To defend his land from future destruction, Jeffry built a bamboo barricade to block access.

Jeffry told Climate Rights International that police and military personnel pressured him to relinquish his land, including by frequently visiting his home. On one occasion, police visited his house at 2 a.m. to demand that he sign a letter that said he would stop obstructing the sale of his land to IWIP, which he refused to sign.

Under pressure, in 2019, Jeffry and the company met but couldn’t reach an agreement because the company refused to recognize the full extent of Jeffry’s ownership of the land, despite Jeffry’s possession of a land certificate. Nevertheless, IWIP continued to cut down trees on his land. Eventually, Jeffry sold his land because he felt that he had no other option.

I was indirectly threatened. I had no choice but to settle with the company. I was trying to defend my rights, my constitutional rights.57Climate Rights International interview with Jeffry, February 10, 2023, Gemef, North Maluku, Indonesia.

Jeffry says that he was only compensated for roughly 25 percent of his land, with the rest of his land taken by IWIP without compensation. According to Jeffry:

I got data from the agrarian state company that states I owned more than 4 hectares. My land measures 41,560.72 m2 by GPS. The company measured 2 hectares then measured again at only 5,000 m2. They only paid me for 5,000 m2.58Ibid.

In a similar case, Maklon Lobe, a 42-year-old man from Gemaf, also claims that his land was illegally excavated and taken by IWIP. Maklon owned 38 hectares of farmland within the current boundaries of IWIP, where he grew cocoa, sago, and nutmeg. Without Maklon’s permission, in 2018 representatives of IWIP cut down his trees and blocked the road to cut off access to his land, leaving Maklon with no option but to sell his degraded land.

Maklon met with IWIP representatives multiple times between 2018 and August 2022 to discuss compensation for his land. Maklon asked IWIP to pay IDR100,000 per square meter (m2), but IWIP only agreed to pay IDR15,000/m2. Despite holding a land certificate, representatives of IWIP only agreed to pay for a portion of the land, taking the rest without compensation.

I owned 38 hectares of land, but they only paid me for 8 hectares. They said that the rest of the money was paid to someone else who claimed they owned the land… The company excavated my land without my consent while I owned it.

Maklon told Climate Rights International that, in a meeting on August 18, 2022 at the Central Halmahera police station, IWIP agreed to pay for his child’s university tuition and construction material to build a dormitory for workers if Maklon accepted the offer of IDR15,000/m2 for eight hectares.59It is becoming common for residents in villages near IWIP to build and manage small worker dormitories to earn an income in the absence of income from traditional livelihoods, like fishing or farming. IWIP’s website states that it aimed to hire roughly 36,000 employees by 2022, and many of those workers live in small one-room dormitories. In addition, mining companies across Indonesia provide scholarships for local youth as part of their corporate social responsibility practices. According to IWIP’s website, it provided scholarship assistance for 77 students at the Tidore Mandiri College of Management and Computer Science in 2023 and has previously provided scholarships for 32 youth from Central and East Halmahera. IWIP, “Contribution to Economy,” n.d., https://iwip.co.id/en/home/ (accessed November 15, 2023); IWIP, “IWIP Gives Scholarship for 77 STMIK Tidore Mandiri Students,” February 23, 2023, https://iwip.co.id/en/2023/02/23/iwip-berikan-beasiswa-untuk-77-mahasiswa-stmik-tidore-mandiri-2/ (accessed November 22, 2023). According to Maklon, IWIP failed to keep its commitment to compensate Maklon at the agreed level, so in January 2023, he filed a lawsuit against IWIP for its failure to compensate, a copy of which was shared with Climate Rights International.

Across Indonesia, the state has failed to recognize customary land and has instead claimed these areas as state-owned assets.60M Safitri, “Dividing the Land: Legal Gaps in the Recognition of Customary Land in Indonesian Forest Areas,” Kasarinlan 30,2 and 31,1 (2015-2016), https://sisdam.univpancasila.ac.id/uploads/repository/lampiran/DokumenLampiran-28062021130151.pdf (accessed December 12, 2023). As of November 2023, the Indonesian government recognized 219 Indigenous territories covering a total of 3.73 million hectares, only about fourteen percent of the estimated Indigenous territories mapped in Indonesia by the Ancestral Domain Registration Agency, an independent, nongovernmental initiative.61HN Jong, “Independent project steps in as government slow to map Indonesian ancestral lands,” Mongabay, November 3, 2023, https://news.mongabay.com/2023/11/independent-project-steps-in-as-government-slow-to-map-indonesian-ancestral-lands/ (accessed November 30, 2023). This failure by the Indonesian government to recognize customary land rights has directly contributed to land conflict for communities in East Halmahera.

Residents in Minamin and Saolat villages, in East Halmahera, told Climate Rights International that, in 2020, a mining company which they believed to be WBN took approximately 140 hectares of their customary land inside the Kao Rahai forest to develop a mining road without informing or compensating the community. While Climate Rights International was not able to confirm whether this company was indeed WBN or another mining company operating in the same area, the WBN mining concession overlaps with the taken customary land. Climate Rights International wrote to Eramet, Tsingshan, and WBN to ask how they compensated landowners, including Indigenous Peoples for their customary lands. While we did not receive a response from either Tsingshan or WBN, Eramet stated:

Besides coastal areas, most of the mining concession is located in a forested area which is owned by the government. To exploit these areas WBN goes through a forestry “borrow and use” permitting process including stringent requirements on compensation, rehabilitation, revegetation, and relinquishment. The local communities do not have legal nor customary ownership of the land in these forested areas.62Eramet letter to Climate Rights International, December 15, 2023, Appendix I.

Paulus Papua, a 58-year-old Minamin Indigenous community leader, said residents learned that the land was being developed when the Minamin forest guardian went into the forest and saw that a mining company had built a road.63Forest guardians are local and/or Indigenous community members who manage and protect forests. For more on forest guardians in Indonesia, see: Mongabay, “Mongabay series: Indonesia’s Forest Guardians,” https://news.mongabay.com/series/indonesias-forest-guardians/ (accessed November 30, 2023). Paulus said that the company was able to take the land because the government failed to recognize the Kao Rahai as customary forest and instead recognized it as state land that could be handed over to companies.

They came without consulting us, no dialogues whatsoever, and they came here stealing from us. It’s our customary land, but the government doesn’t recognize it. Our ancestors lived here long before independence.64Climate Rights International interview with Paulus Papua, March 26, 2023, Minamin, North Maluku, Indonesia.

Artones, a 49-year-old Tobelo farmer from Minamin, also stated that, before the nickel company cleared the 140 hectares of customary forest of Indigenous Tobelo people in Minamin, company representatives did not consult with residents and never paid compensation.

At that time, we got information from our Kapita [forest guardian] that the company cleared the forest for a mining road. There’s no dialogue or any kind of information from the company.65Climate Rights International interview with Artones, May 8, 2023, Minamin, North Maluku, Indonesia.

The prioritization of extractive industries by the government over recognition and protection of customary forests has long been a driver of conflict between Indigenous communities and governmental or private actors.66R Ariadi, “Perampasan Tanah Adat Masih Marak, 301 Kasus Mayoritas di Sulawesi-Kalimantan,” August 9, 2023, https://www.detik.com/sulsel/berita/d-6867939/perampasan-tanah-adat-masih-marak-301-kasus-mayoritas-di-sulawesi-kalimantan (accessed November 30, 2023). For example, the International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWIGA) documented 301 cases of takings of customary land in Sulawesi and Kalimantan between 2019 and 2023.67IWIGA, “The Indigenous World 2023: Indonesia,” March 29, 2023, https://www.iwgia.org/en/indonesia/5120-iw-2023-indonesia.html (accessed October 2, 2023); R Rahman, “Konflik Masyarakat Dengan Pemerintah,” Sosioreligius: Jurnal Ilmiah Sosiologi Agama 2:1 (2017), http://portalriset.uin-alauddin.ac.id/bo/upload/penelitian/penerbitan_jurnal/Konflik%20Masyarakat%20Dengan%20Pemerintah.pdf (accessed September 15, 2023); R Ariadi, “Perampasan Tanah Adat Masih Marak, 301 Kasus Mayoritas di Sulawesi-Kalimantan,” detiksulsel, https://www.detik.com/sulsel/berita/d-6867939/perampasan-tanah-adat-masih-marak-301-kasus-mayoritas-di-sulawesi-kalimantan (accessed September 24, 2023). A 2016 report by the Indonesian National Commission on Human Rights (Komnas HAM) found that the dispossession of Indigenous Peoples from their customary lands contributed to abuses, including forced displacement, violence, and intimidation.68Komnas HAM, “National Inquiry of the Right of Indigenous Peoples on Their Territories in the Forest Zones,” January 2015, https://rightsandresources.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Komnas-HAM-National-Inquiry-on-the-Rights-of-Customary-Law-Abiding-Communities-Over-Their-Land-in-Forest-Areas_April-2016.pdf (accessed July 15, 2023). While the report does not explicitly look at specific sectors like mining, it notes that the arbitrary takeover of indigenous forest areas for the use of other parties, including concessions for mining, logging, and plantations, has led to human rights harms, including threats to the right to a clean and healthy environment, right to education, right to traditional knowledge, right to survival and improved living standards, and right to practice and take part in traditional cultural activities.

Numerous Indigenous Peoples interviewed by Climate Rights International in Central and East Halmahera said that they were not told the purpose of land acquisition or any other details of the project by any nickel mining or smelting companies, and thus were not able to give their full Free, Prior, and Informed Consent.

In the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) filed by IWIP in 2018, the company claimed that it conducted a public dialogue related to the construction of IWIP on May 22, 2018 at a PT Weda Bay Nickel office in Central Halmahera.69While the IWIP EIA is not available online, Climate Rights International has a copy of the document on file. IWIP’s EIA states that this meeting was “attended by agencies and related parties, such as representatives of North Maluku Province Dill, Central Weda District Muspika and North Weda District Muspika, NGOs, as well as community representatives from Lelilef Sawai Village, Lelilef Waibulan Village, Central Weda District and Gemaf Village, North Weda District.”70IWIP EIA, page 4-2. In addition, the EIA states that only five percent of Lelilef residents queried by IWIP had learned about the project from public consultations led by the company, with the majority of residents hearing about the project by word of mouth.71IWIP EIA, page 3-135. No one interviewed by Climate Rights International reported knowing about or attending this public dialogue, and Climate Rights International is not aware of any other public dialogues or consultations hosted by IWIP prior to the approval of its EIA.

Residents interviewed by Climate Rights International claimed that information related to IWIP was not disseminated. According to Max Sigoro, a 51-year-old fisherman in Gemaf,

We residents didn’t know what they were building. The company [IWIP] didn’t explain what the land was for when they were buying land from people.72Climate Rights International with Max Sigoro, February 8, 2023, Gemef, North Maluku, Indonesia.

In Sagea, rumors about a plan to turn the village into an industrial complex with nickel smelters have been circulating for years. While a map about such a plan has been informally shared between residents verbally and over WhatsApp, no reliable information has been provided by the government or company officials, according to residents, and it is unclear where the map originated from. Climate Rights International wrote to the North Maluku Provincial Government to ask how information about the development and expansion of nickel mining and smelting operations and information about long-term spatial planning is shared with impacted communities, but we did not receive a response.

“Humam,” 41, has not heard any official information about plans to industrialize Sagea, yet is concerned that the unofficial information about the nickel industry expansion in the village could harm the future of the village by destroying nature and the local culture of the Sawai people.

We saw [in unofficial information over WhatsApp] the local government’s plan to change Sagea into some kind of housing complex for workers. There are rumors too about building smelters in this area. The problem is we don’t know what it is for. They don’t even show us the mining permit or AMDAL [EIA], let alone explain their activities. So there’s no discussion on this matter.73Climate Rights International interview with “Humam,” March 28, 2023, Sagea, North Maluku, Indonesia.

Mariama, a farmer in her fifties, says she has also heard rumors for years that smelters and workers’ dormitories would be constructed in Sagea. She expressed concern that there has not been any transparency regarding these possible plans or other plans for nickel mining near Sagea.

I don’t want this village to be the next factory. It will destroy the water resources. The land clearance process here started in 2010. They proposed to buy my land last year. But there hasn’t been transparency. They haven’t been transparent on the size of the mining concession.74Climate Rights International interview with Mariama, February 9, 2023, Sagea, North Maluku, Indonesia.

In addition, residents in East Halmahera say they were left in the dark when PT Mega Haltim Mineral (MHM), a separate mining company, started acquiring land without conducting consultations with residents.75While it is unclear when MHM began acquiring land, its mining permit was issued in 2016, and since 2016, 520.65 hectares of the 13,510-hectare concession has been deforested. For more on the size of MHM, see Appendix III. The company offered between IDR2,500 to IDR5,000 (US$0.16 to US$0.32) per square meter, roughly the price of a package of instant noodles.76Climate Rights International interview with Ike, March 25, 2023, Minamin, North Maluku, Indonesia. This price is approximately a fifth to two fifths of what communities in Central Halmahera have been offered by IWIP and other mining companies, which was itself viewed as inadequate compensation.

“Helmi,” 46, lives in Saolat, East Halmahera, and told Climate Rights International that local residents received no information about the purpose of land acquisition by PT MHM, leaving him unsure about how mining operations might impact his way of life. Helmi said the company did not provide documents such as an EIA or a mining permit to residents. According to Helmi:

Mentally, we’re tortured, because we’re scared and restless because we keep wondering about the future of our village…Without dialogues, we don’t know what kind of benefits that we’ll receive. We’ve been here for generations. We have protected nature because our lives depend on nature. If this is all gone, how are we supposed to live?77Climate Rights International interview with “Helmi,” May 8, 2023, Saolat, North Maluku, Indonesia.

Residents who agreed to sell their land to nickel mining companies said they often felt like they had little to no choice in the sale or the level of compensation. Some interviewees stated that they had no choice but to sell their land because they had already lost access to their farm, as the surrounding area had been acquired by a mining company or was now within a mining concession or industrial area.

Nearly everyone who spoke to Climate Rights International about selling their land reported being unsatisfied with the low price that they had been offered or received. Many residents told Climate Rights International that they did not want to sell their land at all, and that even if they received one-time payments of money or goods, this was insufficient to compensate for the lost income and food security provided by their land. Most current and former landowners said they had inherited their land and had planned to pass it on to future generations prior to the arrival of the nickel industry. The loss of their land and the income from farming would, they said, negatively impact future generations of people in Halmahera.

Jamaluddin “Dino,” a 28-year-old man from Sagea, said he felt that he had no choice when PT First Pacific Mining (FPM), a nickel mining company, wanted to acquire his eight-hectares of land. Dino initially refused to sell his land because the price was too low, bult ultimately felt pressured to sell even though FPM did not compensate him for the crops and trees on his land.

All of the surrounding areas were sold, so I had no choice but to sell. There was no place for negotiation over the price. I tried to meet with company officials to negotiate but they said the price was fixed.78Climate Rights International interview with Jamaluddin “Dino,” February 9, 2023, Sagea, North Maluku, Indonesia.

Local residents said that mining companies also illegally cleared land first then compensated the residents later. This practice left residents without room to negotiate because the inherent value of their farmland as a source of crops was already lost.

Felix Naik told Climate Rights International that WBN approached him in 2009 and asked to buy his 2.5-hectare land for IDR8,000/m2(US$0.5/m2).79Eramet provided Climate Rights International with details regarding land acquisition for WBN starting in 2008. In their response, Eramet stated, “PT WBN compensated all claimants even though most of them did not have a legal title.” For the full response, see Appendix I. At that price, Felix and 66 other Lelilef residents refused and asked for IDR50,000/m2 instead. Felix and others protested the sale of their land for a few months before giving up.

We tried everything in our disposal to get what we asked for. We tried communicating with Komnas HAM, sending a letter to the Governor, and including hiring a lawyer to fight for this matter. But all the doors were closed. We can’t fight the giant because they have power and money. So we gave up.80Climate Rights International interview with Felix Naik, May 12, 2023, Lelilef, North Maluku, Indonesia.